Hurricane Outlook and Hurricane Myths

Hello! It’s been a while. March disappeared before our very eyes and we are now healthily within meteorological Spring (which runs from March through May).

This is the beginning of an irregular series that addresses common misconceptions about weather and climate. I’m beginning with hurricanes because last week Colorado State University (CSU) issued their famous seasonal hurricane outlook for this year, so let’s take a look. (For the record, they are also instrumental in a fascinating group forecast website that aggregates hurricane season forecasts from other institutions. I highly recommend taking a look over the next couple of months as it populates for the 2021 hurricane season.)

The take home point from the outlook is that they are forecasting a more active than normal hurricane season in the Atlantic, by about 25-40% (this number varies depending on which of their forecast parameters you use). Interestingly, the core component of their forecast is the expected state of ENSO, which we’ve discussed a couple of times in this newsletter.

Hurricanes are low pressure systems that form over warm water in the ocean. There is an exchange in energy between the ocean and atmosphere, which functions much like the engine in your car. In order for there to be enough energy exchange between the ocean and atmosphere to generate a hurricane, the ocean temperature must be at least 26C (79F) and the winds at the top and bottom of the atmosphere must be, more or less, the same. If the winds at the top of the atmosphere are significantly stronger than those at the bottom (something we call wind shear), they will blow the top of the hurricane off the bottom and disrupt the delicate exchange of energy.

The end of La Niña, and transition towards neutral conditions, most likely mean that wind shear over the Atlantic will be slightly below normal to near normal, and ocean temperatures will be, at least, normal. A perfect breeding ground for hurricane activity. Such a situation may favor enhanced hurricane activity in and around the Gulf of Mexico during the middle-end of hurricane season (August - October), so I wouldn’t be surprised if we saw more activity than usual in that area. See page 32 of CSU’s hurricane forecast for probabilities near you.

Now that we’re talking about hurricanes, let’s take a look at some common hurricane myths to round things out!

Myths

The category of the hurricane is directly related to the storm’s potential danger.

False. Hurricanes are classified using the Saffir-Simpson scale which is based entirely on the storm’s sustained wind speed. Hurricanes are classified as major when their sustained wind speed is at least 111 mph, which corresponds to a Category 3 on the Saffir-Simpson scale. It is true that faster winds in a hurricane will exponentially cause more damage, but wind damage is not the primary concern from a hurricane.

Most hurricane damage is caused by flooding, not by winds. The Saffir-Simpson scale does not account for flooding potential. Flooding potential is dictated by the direction of the winds and level of the tide (collectively called storm surge), and the amount of rain that the hurricane produces. These are nearly always much more important than the storm’s wind speed. It is important to look at storm surge forecasts for landfalling hurricanes in addition to their forecast category.

Hurricanes and typhoons are different.

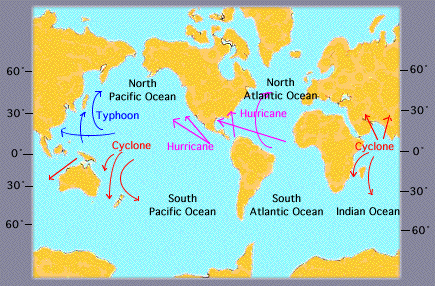

False. The umbrella term for all hurricanes and typhoons is tropical cyclone. Tropical cyclones are low pressure systems (similar to what we experience as winter storms) that are found over water instead of land. In the Atlantic and East Pacific, these storms are called hurricanes. In the West Pacific they are called Typhoons, and in the South Pacific (around Australia) and Indian Ocean, they are simply called Cyclones. There is nothing meteorologically different among hurricanes, typhoons, and cyclones. They are simply different regional names for the same phenomenon.

You should open your windows before a hurricane hits to equalize the air pressure inside your house.

False. This applies to tornadoes also. Opening your windows before a hurricane hits is a bad idea. Your house isn’t air tight, so you aren’t going to allow the pressure inside your house to equalize much quicker with the windows open. Also, an open window will let in water and other debris from outside that a closed window can more easily stop.

You weatherfolk can’t predict the weather next week so I shouldn’t believe your forecast for the next few months!

Kind of false. We will explore long range weather forecasting in the next newsletter and relate it back to the beginning of wine season. Stay tuned!

Kyle